“I’ll be home for Christmas” is the optimistic refrain of soldiers and sailors heading off to war.

“I’ll be home for Christmas” is the optimistic refrain of soldiers and sailors heading off to war.

When war begins, few can imagine it being anything but swift and decisive. It’s only after initial encounters with the enemy that confidence and bravado start to give way to ambivalence and grim determination. Folks back home begin to yearn for days of old and secretly wonder when it will all end. As Carl Sandburg wrote on the first anniversary of Pearl Harbor, “We have learned to be a little sad and a little lonesome.”

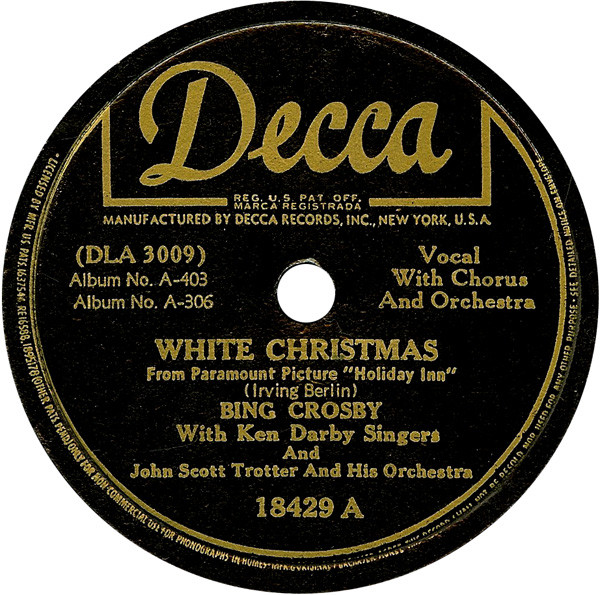

In the fall of 1943, as Americans prepared for their third Christmas at war, Bing Crosby released his recording of a new song, “I’ll Be Home for Christmas,” written by Buck Ram, Kim Gannon, and Walter Kent. It captures this sense of sadness and loneliness in its final line: “if only in my dreams.” This song of yearning was Decca Records’ attempt to capitalize on Crosby’s enormous hit from the year before, “White Christmas.”

Written poolside in Arizona (according to one account) by a Jewish immigrant (Irving Berlin), “White Christmas” is the best selling record of all-time. “We know the song so well, we barely know it at all,” writes the song’s biographer, Jody Rosen.

When Bing Crosby first sang “White Christmas” eighteen days after Pearl Harbor, few people took note of it. It didn’t capture the mood of a nation just gearing up for war. We didn’t yet have ears to hear it.

It was a year later, when Crosby recorded it for Decca and sang it in the movie “Holiday Inn,” when the song become a hit. Even then, it wasn’t the homefront audience demanding it. Rather, soldiers overseas heard the song on the radio and at USO shows and began requesting it.

“Its unorthodox, melancholy melody—and mere 54 words, expressing the simple yearning for a return to happier times—sounded instantly familiar when sung by America’s favorite crooner,” says Roy J. Harris, Jr., in a Wall Street Journal article on the song. Rob Kapilow, interviewed for the article, discusses how the song breaks from tradition by dispensing with a bridge and sticking with the wistful melodic pattern. “Berlin’s opening bars ‘take you up the scale of yearning in their chords,’ and repeating them immediately heightens the impact. ‘Hear the minor chords for ‘listen’ and ‘glisten’?’ asks Mr. Kapilow. ‘It’s heartbreaking.’”

Heartbreak entered our Christmas-season consciousness during the war, and, thanks to “White Christmas,” it is with us still.